More, America

Twenty-Five (More) Founders of the United States of America

Wheatley’s Room with a View on America

In the fall of 1772, a teenage poet sat at her writing table in the attic room of a Georgian townhouse on Boston’s King Street, scribbling couplets with quill and ink. From beneath the room’s sloped walls, she could hear the bell of Old South Meeting House—the great Congregational church where she worshiped alongside the likes of Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and a young Benjamin Franklin, and where crowds often rallied against growing British tyranny. Through the room’s narrow windows, she could see tall-masted ships lilting in the cold waters of Boston Harbor.

It was in that harbor that, in 1761, the poet—then a frail, seven-year-old girl—had been purchased “for a trifle” by Susanna Wheatley, the wife of the merchant John Wheatley, who named her Phillis after the slave ship that carried her from West Africa to Boston. Susanna went to the wharf in search of a house servant. But Phillis soon revealed an extraordinary intellect. The reform-minded Wheatleys tutored her in the Bible, then the classics in Greek and Latin, and English literature including Milton and Pope. She wove this classical education—unprecedented for an enslaved girl—into some of the most prescient poetry about early America ever produced. She soon gained local and then international fame; her mostly white readership was amazed that that an “uncultivated barbarian” could produce such rich poetry, which combined biblical allusions, paeans to great Anglo-American men, with not-so-subtle critiques of the institution of slavery. Freedom came sometime later. John Wheatley emancipated her—or, more precisely, she emancipated herself through her writings—shortly after her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published in 1773, making Wheatley the first enslaved person and the first African American in colonial America to have her writings published.

Wheatley wrote one of the volume’s poems, “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” in the fall of 1772, likely in her attic study, to commemorate the appointment of William Legge (the Earl of Dartmouth) as Secretary of State for the American Colonies. In her poem to the Earl, Wheatley explained that many in New England and throughout America hoped that Legge’s tenure might mark the dawning of a “happy day,” and a softening of what had been the British Crown’s increasingly oppressive attitude toward her colonial subjects.

At the time of his appointment to the highest-ranking imperial office overseeing the colonies, Legge was a seasoned politician, philanthropist, and evangelist. The Methodist reform movements he supported—including the one that led to the founding of Dartmouth College, originally established for the “civilizing and Christianizing” of the “youth of the Indian tribes”—also influenced the Wheatleys’ decision to provide Phillis with her unusually rigorous education. When Legge assumed office in 1772, he enjoyed a reputation for a gentler imperial touch than his predecessors. He had opposed the Stamp Act, which required that items in the colonies—from dice to newspapers—be marked with a costly royal stamp, a policy colonists condemned as “taxation without representation,” and which led to riots that took place just down the street from the Wheatleys’ front door.

While New Englanders like the Wheatleys decried British tyrannical overreach, Phillis Wheatley had experienced tyranny not just as politics, but as a condition written onto her body and biography. After all, she:

Young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat.

…

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

In these lines, Wheatley merged her very American personal trauma—kidnapping, bondage, the pain of separation from her homeland—with America’s own grievances. In the young poet’s telling, both Phillis Wheatley, the enslaved, and John and Susanna Wheatley, her enslavers, knew the sting of authoritarian injustice. Both longed for its end:

No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land.

In 1772, Wheatley’s “No more, America” was both a hope and a demand: that the colonies might “no more” be ruled by tyranny. That instead of iron shackles, ties of brotherly affection might bind New England with Old England and forestall a full rupture from the Crown.

History did not oblige.

Months after Wheatley penned her poem and following the Boston Tea Party, Legge supported the Intolerable Acts, a suite of punitive measures that destroyed any remaining trust between Britain and the colonies. Far from ushering in “no more” tyranny, Legge became one of the imperial architects whose policies accelerated the march toward independence, which America’s Continental Congress formally declared on July 4, 1776.

In retrospect, Wheatley’s appeal to Legge articulated a distinctly American ritual, one that has repeated across the nation’s two-and-a-half centuries. Through their declaration of “no more, America,” the colonists founded—through conflict, loss, and reinvention—America, an independent nation. And ever since, when America has failed to uphold its own promises, Americans have insisted that their country be more American than it has been.

Wheatley is one of the earliest Americans to articulate this ritual of refusal and refounding, which I call “More, America.” She and the other twenty-four figures whom I chronicle in this “More, America” series—one drawn from each decade from the 1770s to 2020s—have carried that ritual of refusal and refounding forward from the nation’s declaration of independence to the present, as the country prepares to take stock of its first 250 years.

More, America on America’s 250th Birthday

This More, America series serves explicitly as counterprogramming to the Trump Administration’s plans for 2026: a full-blown, state-sponsored birthday bash for America, in which the figures like Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin will be further lionized, if not deified. This anniversary need not be—and perhaps must not be—a prepackaged pageant of nostalgia that reinforces a triumphalist vision of America’s founders. Following the historian, journalist, and former Catholic priest, James Carroll, among many others, I call this “thin patriotism,” which treats any criticism of the nation’s past and present as disloyalty, verging on blasphemy. Instead, this anniversary demands a thicker patriotism: what Carroll calls “the peculiarly American demonstration of love of country [which] consists in the readiness to hold the nation to its own higher standard. America, by definition, continually falls short of itself.”

Many of the twenty-five figures whom I will highlight over the next twenty-five weeks embody this kind of thick patriotism. Or to put it another way, many worked within what scholars call the tradition of the American Jeremiad. From Wheatley during the 1770s and the great Pequot Methodist minister William Apess in the 1820s to more recent figures like civil rights icons Ella Baker and Bayard Rustin in the 1950s, Americans have lamented the nation’s failure and demanded that the country finally live up to promise to guarantee life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all. And these figures helped refound America even as they criticized it.

Still, some of the new founders I will highlight don’t fit this mold. Some viewed America as corrupt at its founding and to its core. This is true for Denmark Vesey (c. 1767-1822), the Black freeman and community leader in South Carolina, who was tried, convicted, and hanged for conspiring to lead a slave insurrection. Vesey helped found the Black revolutionary tradition in the United States, which imagined Black freedom not through reform, but through rupture with America. Vesey exposed, with unparalleled clarity, the contradiction at the heart of the republic: a nation founded on liberty that required racial bondage to survive. By organizing—and even more by terrifying—the slaveholding state, Vesey helped found—directly and indirectly—the coercive institutions, racial boundaries, and counter-sovereignties through which the United States organizes itself to this day.

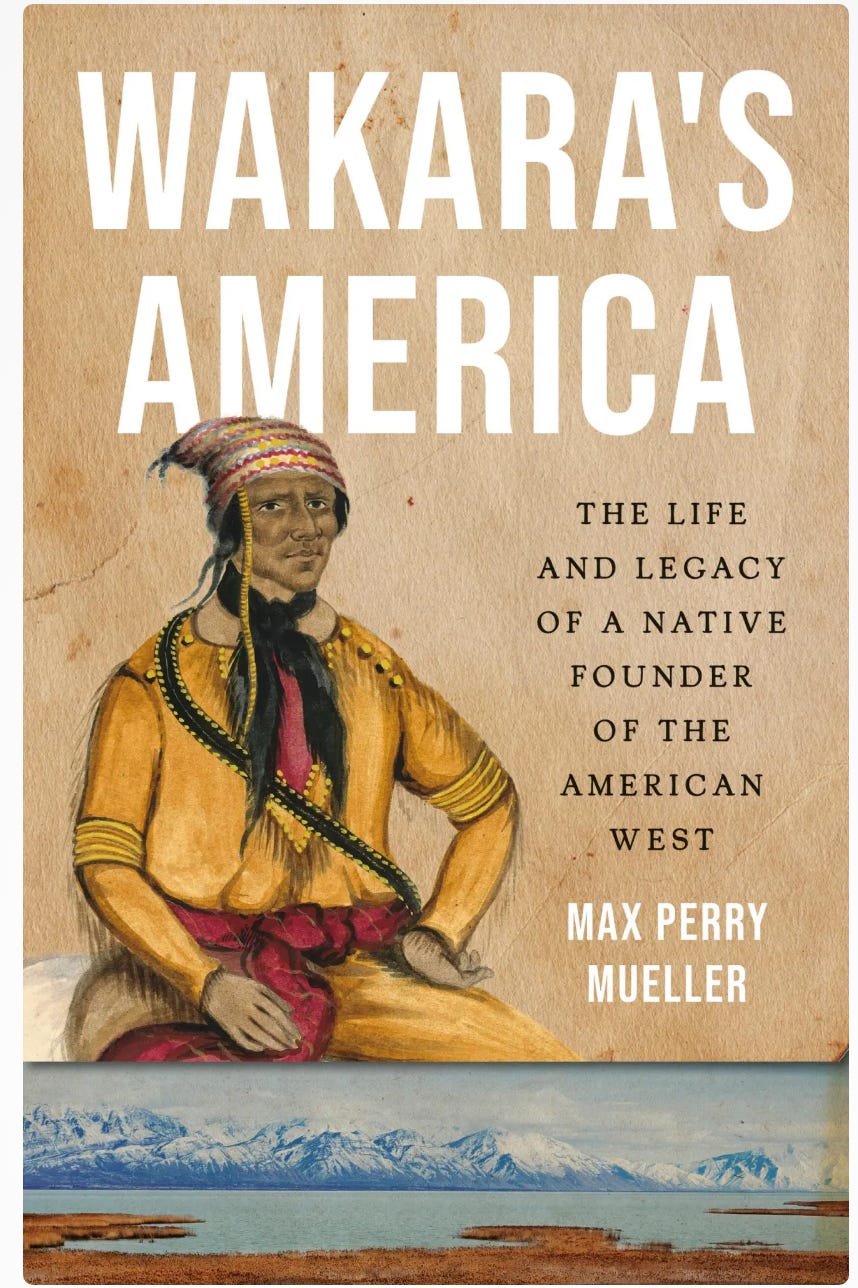

Other founders I will highlight lived and worked outside of what was during their lifetimes the geographical and political borders of the American nation. That’s true for perhaps the most direct inspiration for this project, the Ute leader Wakara (c. 1815-1855), whose life and legacy I chronicle in my recent book, Wakara’s America.

In the 1840s, Wakara was among the most powerful men in what was then northern Mexico, but what is today large parts of the American Great Basin, including Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, and southern California. Among other influences, Wakara’s horse and slave raiding and trading supplied the human and horse power that helped expand American settlements into that huge expanse of land. Wakara’s founding influence on America is not metaphorical, but factual. He was an Indigenous leader whose empire, diplomacy, and violence decisively shaped the American West long before the United States exercised real power there. Understanding him as such a founder exposes U.S. expansion as imperial succession rather than heroic settlement. Wakara’s legacy thus insists that America was founded not only by statesmen, but by Native leaders whose authority, moral complexity, and struggles over land still define the nation.

Of course, the works of other scholars inspire and inform this series, which aims to revaluate when, how, and by who America was founded. To name just a few: W.E.B Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America (1933), Martha S. Jones’sBirthright Citizens, Nicole Hannah Jones’s The 1619 Project, Vine Deloria Jr.’s God is Red, Kathleen’s DuVal’s Native Nations; Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, Howard Zinn’s A Peoples History of the United States, Carol Berkin’s Revolutionary Mothers, Thomas Tweed’s Retelling U.S. Religious History. I could go on and on. In the spirit with this foundational scholarship, More, America aims show that the United States was founded not just on July 4, 1776, but before and after that day, and not just in the room where it happened in Philadelphia, but in many other rooms, like Wheatley’s attic study, as well as on farm and battlefields, in factories and picket lines, on the nation’s shifting borders, and in border crossings.

What to Expect/What You Can Do

To recap: starting this week, and each week until the week of July 4, I will post a profile of a founder of America, one from every decade from 1776 to 2026. Some of the figures will be well-known, others less so. Most will be political figures, organizers, and activists; others will be writers and artists. With their words and deeds, each of these founders told a story about America that reshaped the nation’s imagination, its civic life, its cultures, and its moral and political boundaries. Along with the twenty-five profiles, I will also note other notable figures from the that week’s decade. I will also include founding artists and musicians from each decade.

My twenty-five new founders will not be yours. And that is good. My goal for More, America is to start a conversation, even a debate, about who counts as a founder in American history. After all, who we include in our civic memory shapes the kind of nation we have today and want in the future.

I invite readers to weigh in on my selections and offer their own. In fact, while I have a preliminary list of the figures I will highlight, I’d love to be convinced to change my selections. So comment here with your criticisms of my selections and advocate for your own. And, if you’re willing, discuss this series with others, online or better yet, in person.

Ultimately, as July 4, 2026, approaches, More, America seeks to influence how media outlets, cultural institutions, and classrooms commemorate the nation’s birthday—not through thin patriotism but through a thicker, richer accounting with the nation’s past. This is more important than ever. By embracing new founders whose legacies include acts of creation and destruction and include words of inspiration and damnation, we gain a more honest account of how America was actually made as an ongoing process. We also gain a clearer vision of the kinds of founders we need in an era when the nation, on the brink of political collapse, must again imagine itself anew.