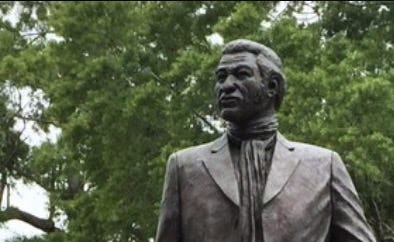

Denmark Vesey (1820s)

More, America: Twenty-Five (More) Founders of the United States of America

Note: This is the sixth in a series of twenty-five new founders of America—one for each decade from the 1770s-2020s—whom I will highlight as part of my series, More, America.

Black Charleston: A City that Could Not Sleep

Even before the sun rose over Charleston, South Carolina, in late spring 1822, the heat and humidity settled down like a thick blanket, pressing the smells of the harbor—salt, fish, and human bodies at work—into city’s narrow streets. There, hundreds of enslaved men carried loads of cotton, rice, and lumber between warehouses and wharves. The much smaller number of free Black men and women dashed between their own places of work, carrying the tools of their trades—cooperage, carpentry, and sewing, for example—on their belts or in bags swung over their shoulders. They also kept their heads on a swivel, conscious of eyes tracking their every movement.

By nightfall, the approximately 14,000 Black residents of the city—more than half of Charleston’s population—settled down. But many did not sleep. Small group slaves as well as free men and women, of which there were about 1,500, gathered in the corners of kitchens, back rooms, and church lofts. There, in hushed voices, they talked of scripture and of freedom in a republic that insisted it was born from liberty. Some—scholars still debate how many—also talked of Haiti, of timing, and of weapons. They asked if God would bless their hands if they struck out with violence in the name of freedom.

A fifty-five-year-old formerly enslaved carpenter named Denmark Vesey led many of these furtive, late-night conversations. Two decades before, Vesey had purchased his own freedom and then set to work freeing others. A devout Christian and lay preacher, he read in the Bible’s pages not a divine justification for Black people’s enslavement, as many white ministers and masters taught. Instead, he found a message of freedom that, unlike the American revolution, demanded liberty for all God’s children, not just the white ones. Vesey also swam in currents of the Black Atlantic’s news and ideas, which envisioned Africans, and Africans in diaspora, as only temporarily anchored to a system of bondage or under the heel of European colonial rule. Vesey and his allies pointed to the revolutionaries on the island of Saint-Domingue not too far from their own port city. Decades before, leaders with names like Vincent Ogé and Toussaint Louverture had, in fits and starts, organized and armed themselves, before successfully overthrowing their enslavers and oppressors to found Haiti, the world’s first Black republic. They could do the same, Vesey told his allies. They could strike down Charleston’s slaveholding class, seize the city, and escape their American Egypt altogether.

Vesey’s revolution ended before it began. Vesey and his allies were betrayed by a few enslaved men who had sat in on some of the planning meetings, but later told their masters and city officials about the plans. In early summer 1822, a citizens’ militia rounded up suspected participants, including Vesey. After a series of secret court hearings, which centered on coerced or manipulated testimony, dozens of men were convicted, then deported or hanged, including Vesey. Beyond those found guilty, white authorities meted out collective punishment, leveling Black Charleston’s churches and businesses, which were blamed for serving as incubators for the revolt. And the city created a municipal guard to surveil the enslaved and free Black population, one precursor to modern-day American policing.

For much of the twentieth century, historians debated whether the Vesey-led “conspiracy” had occurred at all. Some argued that the plans had been exaggerated or even invented by white authorities eager to justify the repression of a growing free Black population in Charleston. Today, the scholarly consensus is that Vesey did in fact plan a slave revolt, even if the revolt’s actual details can never be fully known. Still, the evidence—mostly reports of the testimony given at the secret court hearings—are at once detailed, graphic, and compromised. What they reveal is not a spontaneous Black fantasy or a manufactured white panic. Instead, Vesey’s would-be slave revolt reveals a sustained Black culture of resistance that frightened white Charleston because it was plausible. The city’s response—destroying Black churches, tightening surveillance, and executing dozens of Black men—confirms how seriously white officials took the threat.

Yet what has also emerged from the written archive of the conspiracy is a portrait of Denmark Vesey, a founding visionary of a different kind of America. In Vesey’s revolutionary new nation, Black people would not seek inclusion within the existing white American republic, in which the enslaved and freemen would have to depend on white liberal benevolence or the gradual awakening of white conscience. Instead, this new nation’s founding act would be a violent, divine judgment against enslavers. Its second act would be the realization of Black liberty based on the divine premise that freedom was already theirs by birthright.

Vesey’s revolt never came to be. But it still forced the early American republic to reveal what it would do to preserve slavery when faced with perhaps its most devastating and righteous critique: a coherent, collective, Black claim to revolutionary freedom.

Vesey’s Black Atlantic World

Denmark Vesey’s life was a product of the Black Atlantic world that made the Charleston slave revolt possible—but its actual implementation improbable. The child who would become Denmark Vesey was born into slavery around 1767 on the Danish colony of St. Thomas. His parents were likely enslaved people stolen from West Africa; the boy’s first language might have been Akan or Mandé. In his early teens, the boy was purchased by the Bermudian sea captain Joseph Vesey, who renamed him Telemarque. As he traveled with Joseph Vesey between the Caribbean islands and the ports of what became the southern United States, Telemarque was exposed to a mix of languages, political news, and views—a kind of indirect education rarely experienced by most enslaved people in the American South. Telemarque was sold briefly in Saint-Domingue but was returned to Vesey because he suffered epileptic fits. Some scholars believe that Telemarque faked the condition to escape the harsh life of plantation slavery on the island. Fluent in French, Spanish, and English and a sophisticated reader and writer, Telemarque served as his master’s translator and secretary. The captain eventually retired in South Carolina where in 1796 he wed the owner of Lowndes Grove, a plantation outside of Charleston, and where Telemarque was enslaved as a servant.

In 1799, Telemarque won a city lottery and used the proceeds (about $30,000 in today’s dollars) to purchase his freedom. He renamed himself Denmark Vesey, his first name taken from his St. Thomas birthplace’s Danish colonial ownership. During the first decades of the 1800s, Vesey established himself as a skilled carpenter, moving between white households, workshops, and public spaces in ways that exposed him to constant surveillance but also to information. He lived among both enslaved and free Black Charlestonians. Vesey was legally free in a society increasingly hostile to the very existence of free Black people. This included his own family members, whose freedom he tried, and failed, to purchase.

Imagining the End of Slavery—and of America as It Was

During this time, Vesey also began to envision alternatives to America’s hypocritical founding, as Edmund Morgan has argued: freedom for landowning white Americans purchased by the slave labor of Africans (and the displacement of Native Americans). Vesey gravitated to a particularly Black form of Christianity. He became a lay preacher and leader within the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the Black congregation founded in Philedephia in the late eighteenth century by free Blacks seeking to create Black-run institutions independent of white control and surveillance. Methodism appealed to many Black Charlestonians, including Vesey, because of its emphasis on spiritual equality, lay preaching, and direct access to scripture. In the Bible, Vesey and other Black Methodists read not divine edicts that slaves should obey their masters (Ephesians 6:5), as white ministers taught. Instead, they found—and preached—a model of divinely sanctioned liberation, namely the story of the Israelite exodus from their bondage in Egypt.

At the same time, Vesey was steeped in revolutionary political language, including the Declaration of Independence, whose claims he reportedly quoted back to white Charlestonians. But the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, loomed largest of all. During the decade-long revolt on Saint-Domingue, Charleston was flooded with white refugees and some of their slaves. The city was also saturated with Black sailor talk about Black sovereignty in Haiti. Vesey followed these developments closely. Haiti demonstrated that enslaved Black people could, in fact, overthrow their enslavers and create a Black republic in the Atlantic world. Vesey fused these influences—biblical justice, revolutionary rhetoric, and the Haitian example—into a coherent worldview in which Black violent resistance became a moral necessity.

And yet by the late 1810s, Denmark Vesey’s political vision for a freed Black America took shape alongside a broader national foreclosure of that possibility. The Missouri Crisis of 1819–1821 made it clear that the expansion of the United States depended on the expansion of slavery. At home, Vesey felt how slave power tightened its grip. Charleston officials doubled down on racial discipline: tighter controls on Black mobility, heightened suspicion of Black churches, and mounting fear that revolutionary ideas were circulating among free Black men and women faster than they could be contained. Vesey’s America took shape in the space that these anti-freedom developments accelerated. If America would not imagine a future without slavery, Vesey would imagine an end to America as it existed.

Before it was betrayed, the Vesey-led plan for the Charleston slave uprising emerged less as a single documentable plan than as a web of conversations, commitments, and moral preparation that unfolded over months, and possibly years. By late 1821 and early 1822, a circle of enslaved and free Black men in Charleston, many connected through carpentry, artisanal labor, and church life, began to plan a coordinated attack against Charleston’s slaveholders. Vesey may have set a tentative date of July 14 to coincide with Bastille Day, a symbolic link to the transatlantic revolutionary era. The plan was to seize weapons from the city arsenal, kill enslavers in the city and outlying areas, and then escape by ship to Haiti.

Betrayal, Trial, and the Violence of the Archive

This plan came undone through betrayal from within Charleston’s Black community, though historians among Manisha Sinha and others stress that “betrayal” itself must be understood in the context of the precarity of Black life in the American South at the time. In May 1822, enslaved men approached white authorities with information about the planned uprising, setting off a wave of arrests. The motives of these informants were opaque. Some may have hoped to protect their own families from reprisals; others may have feared collective punishment or doubted the feasibility of the plan. Yet the speed with which city officials moved—rounding up dozens of men within days—reveals the seriousness with which the white, slave-owning class treated the threat of such an uprising.

In June, Charleston officials set up secret tribunals, headed by a newly authorized Court of Magistrates and Freeholders. The public was excluded from these hearings, though the owners of the accused enslaved men were allowed to attend. The magistrates relied on testimony that was likely coerced under threat of torture or even death. The defendants were denied the right to confront their accusers. Historians of Vesey have emphasized that these tribunals did not merely discover the conspiracy; they produced it in a form legible to white authorities and the white public.

At the beginning of July, the first records of the tribunals were published and defended by Charleston newspapers. In these reports, timelines were fixed and roles clarified. Vesey was cast as the mastermind and found guilty of attempting “to raise an insurrection” in South Carolina. The official report portrayed him as a fanatic who had riled up his co-conspirators by quoting scriptures, which not only described slavery as contrary to God’s law, but required the enslaved “to attempt their emancipation, however shocking and bloody might be the consequences.”

On July 2, Vesey, along with five enslaved men, was executed by hanging. All six of these men went to the gallows without a public confession. In the weeks that followed, there were more arrests and quick verdicts. In total, sixty-seven men were convicted of conspiracy. More than thirty were deported, including Vesey’s own enslaved son Sandy, who was likely sent to Cuba. Thirty-five Black men were hanged. Charleston authorities also passed new laws aimed at suppressing Black literacy and independent Black worship. The AME Church was burned to the ground. The authorities also intensified patrols and restricted Black movement and assembly, including passing a law that required Black sailors from ships docked in Charleston to be kept in the city jail while their ships were in port. Four white men were also convicted of misdemeanor charges of inciting slaves to revolt. They were fined, and one white man spent a year in prison. The tribunal leaders warned the public that harsher punishments would be handed out if other whites attempted to support future slave uprisings. In the end, white Charleston’s response to the Vesey conspiracy did not merely seek to punish those it found guilty. It attempted to extinguish the conditions—including potential white abolitionist support and Black institutional support—that had made such a conspiracy imaginable.

Vesey’s Afterlife and America’s ongoing Reckoning

In the decades after 1822, white Charleston worked to forget Denmark Vesey. White writers reduced him to a cautionary tale or erased him altogether. Yet Black Charlestonians carried his legacy forward, embedding it in stories of faith, betrayal, and courage. This remembrance included Vesey family members who remained in the city. His son Robert helped lead secret religious services and, after the Civil War, helped rebuild Charleston’s AME Church, now known as Mother Emmanuel.

Until the twenty-first century many white historians treated Vesey as a historical footnote—an exaggerated threat built out of “angry talk” from enslaved people who could not possibly mount a revolutionary freedom fight of their own. Black activists and intellectuals, including Frederick Douglass, remembered Vesey differently. His legacy circulated as a symbol of uncompromising resistance. He appeared alongside figures like Nat Turner and Toussaint Louverture as proof that enslaved people were not passive victims but visionaries of freedom’s cause who were willing to confront slavery at its roots.

Among historians today, Denmark Vesey is widely understood as a serious political actor rather than a fanatic or fabrication. The old question—Did the conspiracy really exist?—has largely been replaced by more productive questions,such as how repression and coercion shaped the historical archive of slavery, and what Vesey’s story reveals about Black political thought in the early republic. In answering these questions, scholars emphasize Vesey’s literacy, his interpretation of Christian scripture, and his place within Atlantic revolutionary currents, while remaining cautious about the plot’s actual scale and readiness.

More, America

Denmark Vesey forces a reckoning with a founding tradition that the United States has long tried to suppress: the tradition of righteous judgment against one of America’s founding sins. Vesey did not ask to be included in the white American republic. Instead, he measured that nation against its own revolutionary declarations—biblical and republican alike—and concluded that the perpetuation of African chattel slavery in a land claiming to be the home of free men and women placed America under divine condemnation. Vesey’s America was not a promise deferred, but a verdict rendered.

Vesey’s America and the America that enslaved him, killed him, and attempted to destroy the Black religious and intellectual world that gave him purpose met again in the sanctuary of Charleston’s Mother Emmanuel on June 17, 2015. During a Bible study, a young white supremacist murdered nine Black Americans, including a South Carolina state senator who was also the church’s pastor, the Reverend Clementa Pinckney. The murder of the Emmanuel Nine demonstrated that the logic of Vesey’s enslavers and judges—a logic premised on the belief that Black people constituted such a threat to white order that Black people must be surveilled, silenced, and killed in the name of preserving it—remained alive almost two centuries after Vesey’s planned uprising.

Denmark Vesey stands as a founder of an alternative nation to the America built on white supremacy—one in which literacy became power, religion became indictment, and liberty and justice were for all, or liberty and justice were for no one at all. Charleston’s secret courts killed Denmark Vesey to prove that Vesey’s America could not exist. But those courts failed. Vesey’s America lived on in the Black churches that rose from the ashes, in the abolitionist struggle that emerged in the South as well as the North, and in the struggle for Black civil rights from Selma to Chicago.

Today, Vesey’s America also lives on in whistle brigades, school bus patrols, and food deliveries—like those happening on the streets and neighborhoods of Minneapolis—in which Americans of every background fight and die to defend their fellow Americans whom the current American government is trying its hardest to surveil, silence, and disappear.

Who would you choose for the 1830s?

Here are some possible candidates:

Nat Turner (1800–1831). The enslaved preacher whose 1831 rebellion in Virginia exposed the theological and political violence required to sustain slavery in a republic that claimed liberty of conscience as a founding principle.

Omar Ibn Said (c. 1770–1864). The enslaved Muslim scholar whose Arabic autobiography unsettled American assumptions about race, religion, and intellect, forcing the Christian republic to confront the global and Islamic dimensions of its slave system.

David Walker (1785–1830). The Black abolitionist whose Appeal shattered the moral legitimacy of the United States by declaring slavery a crime against God and humanity—and by insisting that resistance, not patience, was the measure of true American freedom.

Maria Stewart (1803–1879). The free Black woman whose public lectures in the early 1830s fused Christian prophecy, racial justice, and women’s political voice, challenging a republic that excluded Black people and women from its definition of citizenship.

Black Hawk (1767–1838). The Sauk leader whose resistance to removal in the Black Hawk War exposed the United States’ founding commitment to territorial expansion over treaty law, Indigenous sovereignty, and moral restraint.

Works on Denmark Vesey

Douglas R. Egerton. He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

Michael P. Johnson. “Denmark Vesey and His Co-Conspirators.” William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2001): 915–976.

James O’Neil Spady. “Power and Confession: On the Credibility of the Earliest Reports of the Denmark Vesey Slave Conspiracy.” William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 2 (2011): 287–304.

Philip D. Morgan. Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Manisha Sinha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Julius S. Scott. The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. New York: Verso, 2018.